(First appeared in Vietnamese in The Saigon Times, print edition on 14 October 2021, and online edition on 16 October 2021.)

As reported by Saigon Economic Online, a Thai investor recently sued Aqua One (a company associated with Mrs. Do Thi Kim Lien, who is the Chairwoman of the Board of Directors) and Mr. Do Tat Thang at the Vietnam International Arbitration Center regarding the purchase of shares in Duong River Surface Water JSC (Song Duong) (1).

Based on publicly available information (2), this article briefly discusses several issues related to this specific case and the general practice of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in Vietnam.

Table of Contents

Mitigating Risks Through Contracts

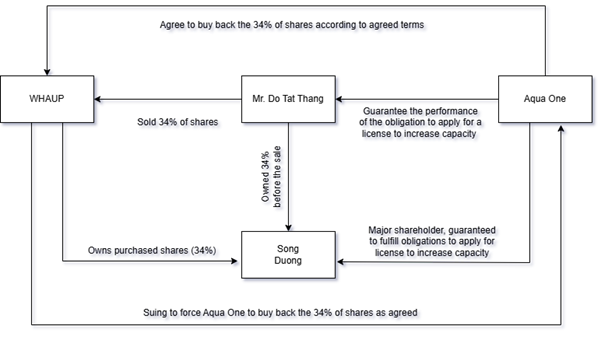

In October 2019, the Thai party purchased a 34% stake in Song Duong from Mr. Do Tat Thang (who directly owned shares in Song Duong). According to the contract, if by October 25, 2020, Song Duong had not obtained the investment certificate to increase the capacity of the Duong River Surface Water Plant from 300,000 to 600,000 cubic meters per day, Aqua One (a major shareholder of Song Duong and the guarantor for Mr. Thang) had to buy back all those shares from the Thai party. In November 2020, the Thai party requested Aqua One to fulfill this obligation by June 7, 2021. Since Aqua One has not repurchased the shares, the Thai party has initiated arbitration proceedings.

From my experience, the Thai party’s commercial purpose in buying the shares was for the Duong River Surface Water Plant project to be implemented with double the capacity. Therefore, the risk for the Thai party when deciding to buy was that Song Duong would not be granted permission to increase capacity to that level.

There are at least two ways they could mitigate this risk. One is to require Song Duong to obtain the permit before they pay (all or most of) the purchase price. The second way is to accept the payment and set a deadline for Song Duong to obtain approval for the increased capacity. If the permit is not obtained by that deadline, someone will have to buy back the shares from them.

Here, the Thai party chose the second method, although the first method is more secure. They had reasons to do so, such as believing that with Mrs. Lien’s connections, obtaining the permit would be easy. Or they accepted the risk in exchange for a lower purchase price or to secure the contract from other potential buyers at that time.

Anyway, it was a commercial calculation; the important thing is that they recognized and mitigated the risk through the contract. The party required to buy back the shares could be the seller (Mr. Thang) or someone with greater financial capability (Aqua One). The Thai party might also have retained part of the purchase price, possibly in a jointly managed bank account.

Let’s talk about Commercial Law

The price Aqua One must pay to repurchase the shares is the amount the Thai party paid plus a sum referred to as the “Carrying Cost.” It is unclear how this additional amount is determined, but it likely includes interest calculated at a certain rate on the amount the Thai party paid.

Does this additional payment fall under the 8% limit on the value of the breached contract obligation? The answer should be: No. The share repurchase agreement creates a conditional obligation. Accordingly, Aqua One is obliged to buy the shares at a certain price and time, provided Song Duong does not obtain the permit by the agreed deadline.

Failure to obtain the permit is not a contract breach. It is an event that triggers the repurchase obligation. This agreement between the parties complies with Article 284 and related provisions of the Civil Code.

In fact, the entire Commercial Law should not be applied to share purchase agreements. The reason is that this law primarily governs contracts for the sale of goods and the provision of services. Shares are neither good nor services. Therefore, applying this law’s provisions (such as delivery, warranty, and transportation) to share purchase agreements would be inappropriate.

Conversely, the common terms of share purchase agreements, even if localized from Western contract templates, can be compatible with the general provisions of the Civil Code (3).

Hesitant Steps

Recently, the Science and Life newspaper of the Vietnam Union of Science and Technology Associations published an article stating: “After only two years of cooperation, Thailand’s WHAUP Company ‘retreated’ from the Duong River Surface Water Plant project. In fact, the plan to increase the plant’s capacity was ‘interrupted’ amid numerous controversies, and the senior leadership of Hanoi in the previous term all lost their positions”(4). If what the article says is true, it highlights another business deal that failed when officials were “ousted.”

Land, public assets, infrastructure, public services, and resources are all limited. Permits for projects in these areas are therefore scarce, difficult to obtain, and thus more expensive. It is not unusual for foreign investors to rely on, associate with, or cooperate with rising local entrepreneurs to obtain permits. But we can draw a few conclusions from this phenomenon.

First, if the amount foreign investors pay is significantly higher than the intrinsic value of the business just to get permits faster, easier, or with more privileges, they will later use every means to recover that excess amount. This is understandable at first glance because business needs to be profitable.

That’s true, but when privatizing public services, investors may aim to recover capital as quickly as possible, often not by improving quality but by raising prices, reducing actual capacity, or limiting quality. Consequently, the public, already with few choices in using public services, ultimately bears the burden of the large amounts’ investors pay. Hence the saying: public resources are enjoyed by private entities, while the people bear the cost.

Second, foreign investors will look at cases like this to assess the risk of investing in Vietnam, especially in the aforementioned areas. They may still invest, taking a high-risk, high-reward approach or perhaps with objectives other than profit. But legitimate investors from countries with a tradition of adhering to the law might hesitate and reconsider.

By Ngu Truong

—————–

(1) Van Phong, “Thai Company Takes Shark Lien’s Water Business to Arbitration” (October 7, 2021) (2) Including WHA Group’s letter to the Chairman of the Thai Stock Exchange, dated September 30, 2021, announcing the initiation of arbitration proceedings in Vietnam, https://www.set.or.th/set/pdfnews.do?newsId=16329590281810&sequence=2021106612 (accessed October 10, 2021). (3) On this issue, the author provides detailed commentary in the book “Essentials of M&A Legal Practice” published by Thai Ha in cooperation with Industry and Trade Publishing House at the end of 2018 (reprinted). (4) Minh Quang, “Duong River Surface Water Plant’s Expansion Plan Stalled, Investor ‘Withdraws'”, https://khoahocdoisong.vn/lo-nhip-quy-hoach-nha-may-nuoc-mat-song-duong-nha-dau-tu-thao-chay-181292.html (accessed October 10, 2021).